For the last few weeks, I start every morning lying down on the floor. My shoulder blades poke the smooth cork mat beneath me, and slowly, I punch my arms up towards the ceiling. The bony wings of my back float away, and I catch myself. Will them down and count to five.

This is all part of my stretching homework. Back in September, I begrudgingly made a PT appointment at the behest of my sister. I was playing flute quite a lot, and each practice session always ended with an acute sting then numbness that radiated from my left wrist. Seeing a specialist, though, felt futile when the most glaring and useless solution in my mind was to simply stop.

Never did I think I would be playing Mozart in an examination room. But there I was, running through thirds while the doctor and residents assured me they had no place judging classical style, only observing my movements. They pointed to this or that part of my torso, guiding my arms here and there, before telling me my fate.

I was diagnosed with a weak back.

Turns out, twenty years of caving over a metal rod produces a shockingly underdeveloped set of upper back muscles. In fact, my fixation with my wrist overlooked a long line of influence – nerves could be traced from my hand to elbow to bicep to shoulder to collarbone. And anywhere along that path might be pinched or crunched. Working on the muscles between my shoulder blades would slowly give them the power to contract, pulling my chest open. When I brought my flute to my face in this way, my entire arm would lengthen, returning space to my weary wrist.

It’s been a year of these beautiful, tangential resolutions. Last November, I was depleted to a pulp from a job that sucked the spark out of me. It preyed on my most anxious instincts as I put in more, more, more of myself. I stopped playing the flute. I couldn’t bring myself to cook. I began to harbor resentment. It felt like everything in me was crumpling. This was the pain in my left wrist that I refused to address. This was the numbness I told myself I should just push through. Stopping, it seemed, was not an option.

A part of me must have known that quitting was just temporarily wrenching my wrist back into place. What would I actually see when I traveled the length of my arms, through the muscle and the fat and the tendons? What true problem was seeded years ago, tangled up into the pain at hand?

I quit on January 17. And on January 18, I started an 8-week writing class, partly because I wanted something to do, and mostly because I had not been able to write for nearly a year. I was obsessed with making sense of what was happening to me, but unable to remember what previous versions of myself actually felt like. How could I have undergone this transformative COVID-induced smell journey, and yet, have so little recollection of it now? If I couldn’t place myself back in my thought process from five years ago, how could I figure out what was next? What proof would I have that I wasn’t barreling backwards? I entered the paradox of writing without remembering – what was there to say?

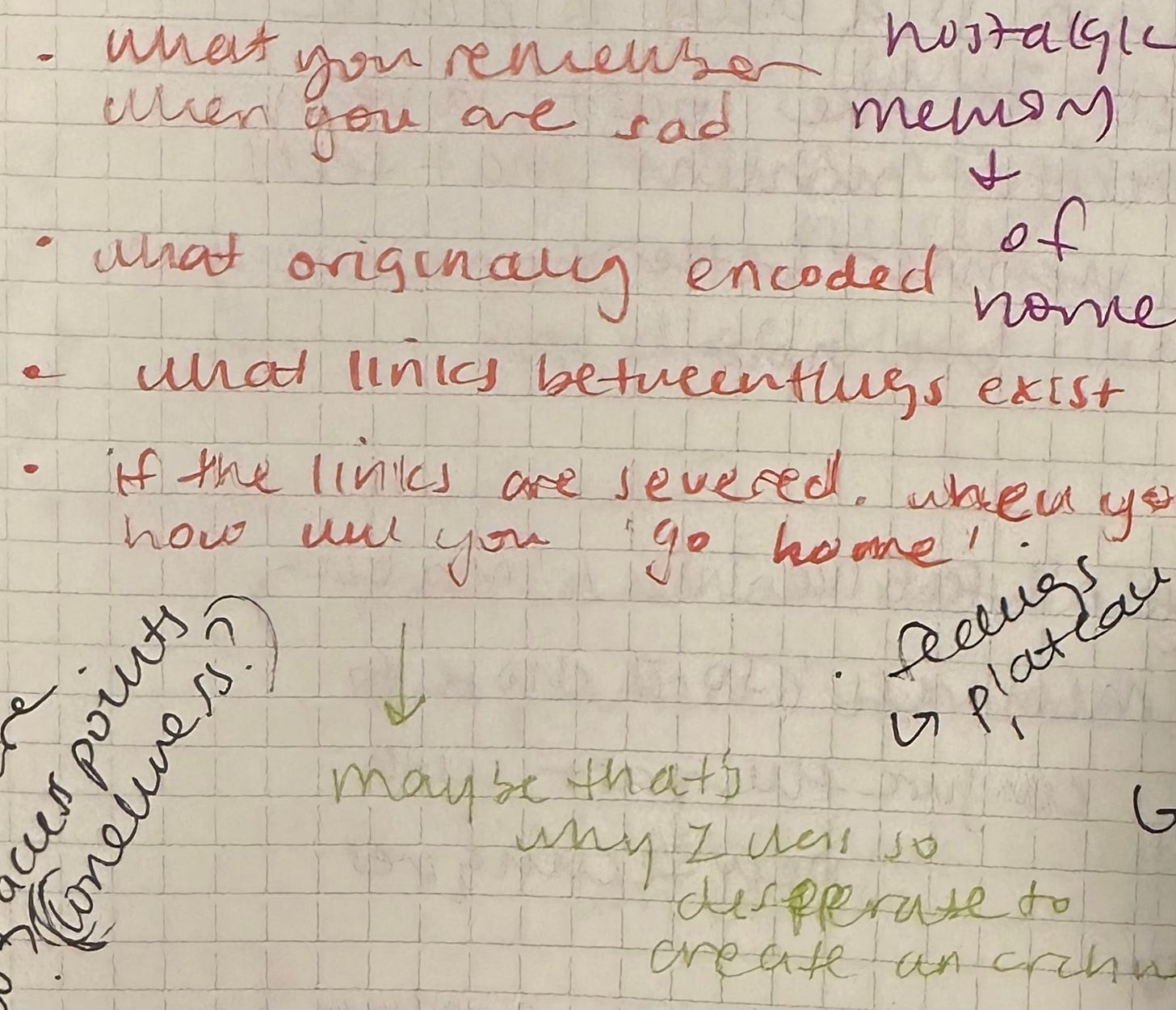

For days, I made pages and pages of notes on nostalgia, memory, and the obscured line between before-during-and-after. Eventually, I threw up my hands and figured that the most important thing to do was to keep moving. So, I read books. Took myself to museums. Built some bookshelves. Painted. Rearranged my room. Cleaned my kitchen cabinets. Posted teaching fliers in every café down 5th Avenue. I told everyone in my path that I was seeking something.

And somehow, after swirling this way and that, things started to crystalize. I played flute on a local series. I got a few more private students. I was a substitute music teacher at a private school. I got called by previous employers for part-time jobs that fueled the bravery and flexibility to dive further into bubbling musical goals. I dreamt up a proposal and applied for a grant. I took a professional audition for the first time and got way further than anticipated. I had an opportunity to record an album. I brainstormed and mused and arranged parts and rehearsed and recorded and put it into the world. It got 1.6 million streams. I planned a release show at my favorite place in New York, a food bookstore where I’ve made some of my closest friends. I wrote a script for the show that centered storytelling along with music. It was about nostalgia and this weird obsession I’ve had with remembering and the impossibility of going backwards or forwards or anything except outwards in this life. My family came to hear me for the first time in five years. I cried tears of gratitude and joy. I felt alive with possibility and excitement and creativity.

You see, I’ve been stretching. I’ve been working my back muscles, supermanning each morning so that nearly a year later, I finally understand my true pain point, the muscles I hadn’t thought to strengthen. Through the blessing of distance and time, I have opened myself up, pried myself out of huddled fear, and faced what I really needed to resolve: that all my life, all I’ve truly wanted, was to be an artist.

Three weeks ago, I started a new part-time job with an old employer. As I walked down familiar hallways, I began seeing double. A black-bobbed, Peter-Pan-collar-wearing specter shadowed my every step. Her translucent form overlaid mine as we visited the IT office to pick up a laptop, Human Resources to fill out my tax forms, and the mail room, which I learned, upon several confused rotations, had since moved to another floor.

Her potent presence was puzzling me when a beloved coworker I’d met 5 years ago – who now follows this publication – approached from down the hall. I assumed he would collate this ghost and I with the forgivable “You’re back!” lobbed at me all day. Instead, he smiled and said:

“I haven’t seen a blog from you in a while.”

This simple statement has pulled me out of retirement. Because in pointing out this distance and time, my colleague reminded me that in doing everything but writing, I have perhaps finally created enough space to make sense of myself again.

I’m reading this esoteric book by Clarice Lispector called Água Viva. It’s a fictional, meandering diary of Lispector as a painter. She writes at one point that, “To live this life is more an indirect remembering than a direct living.” I can’t say what Lispector’s analogous wrist pain was, but it seems she knew it had to be resolved from afar. Growth is perhaps less about holding all versions of ourselves at all times, and more like this constant mitosis in which we must perennially mapping our split selves onto another as proof of transformation. I may be returning to the same circumstances, to the same hallways, and to the same dreams as before, but I am so undeniably sure that this specter and I are different. This time, I’m not forcing myself into shapes that I cannot sustain. This time, I’m trying with all my might to trust that the work I’m doing will hold me up. I’ve proven to myself that even if I can’t see it now, as long as I keep reaching upwards to the sky every morning, I’ll someday remember – even if indirectly – the enormity of my expansion.

So, in many ways, I have been writing. I’ve been absorbing and piecing together and listening and sensing and resolving and stretching in this beautiful year of tangential remembering, forgetting, and remembering again.

All of which is to say, I have, simply – and finally – been living.

The musical storytelling show I wrote was proof to myself that I was opening up again. I’d love if you would read about it and watch it here. Let me know what you think.

I’m 3 months late to reading this (it’s been sat unopened in my inbox until now!), but I’m so glad you found your way back to writing—on and off the page. This reminded me of a quote from Any Human Heart by William Boyd you might like, “We keep a journal to entrap that collection of selves that forms us, the individual human being.” Can’t wait to see which versions of you appear on the page (screen) next ✍️

beautifully written <3