First of all, I’m really proud of myself for keeping this up (3 posts in!) I don’t plan these posts and attempt to make this a space where I write through what I am truly feeling when it arises. I sort of wrote about that feeling in today’s newsletter, and even though it’s not directly about food, it relates to this new journey of mine and to thoughts that I’ve tried - and am still trying - to put my finger on. These are usually transcriptions with a few edits of my morning journalling, so they represent feelings that are mostly unfiltered. Thank you for letting me exist in your minds on my own terms.

Subscribe here if you made it to this page somehow and are interested in staying tuned.

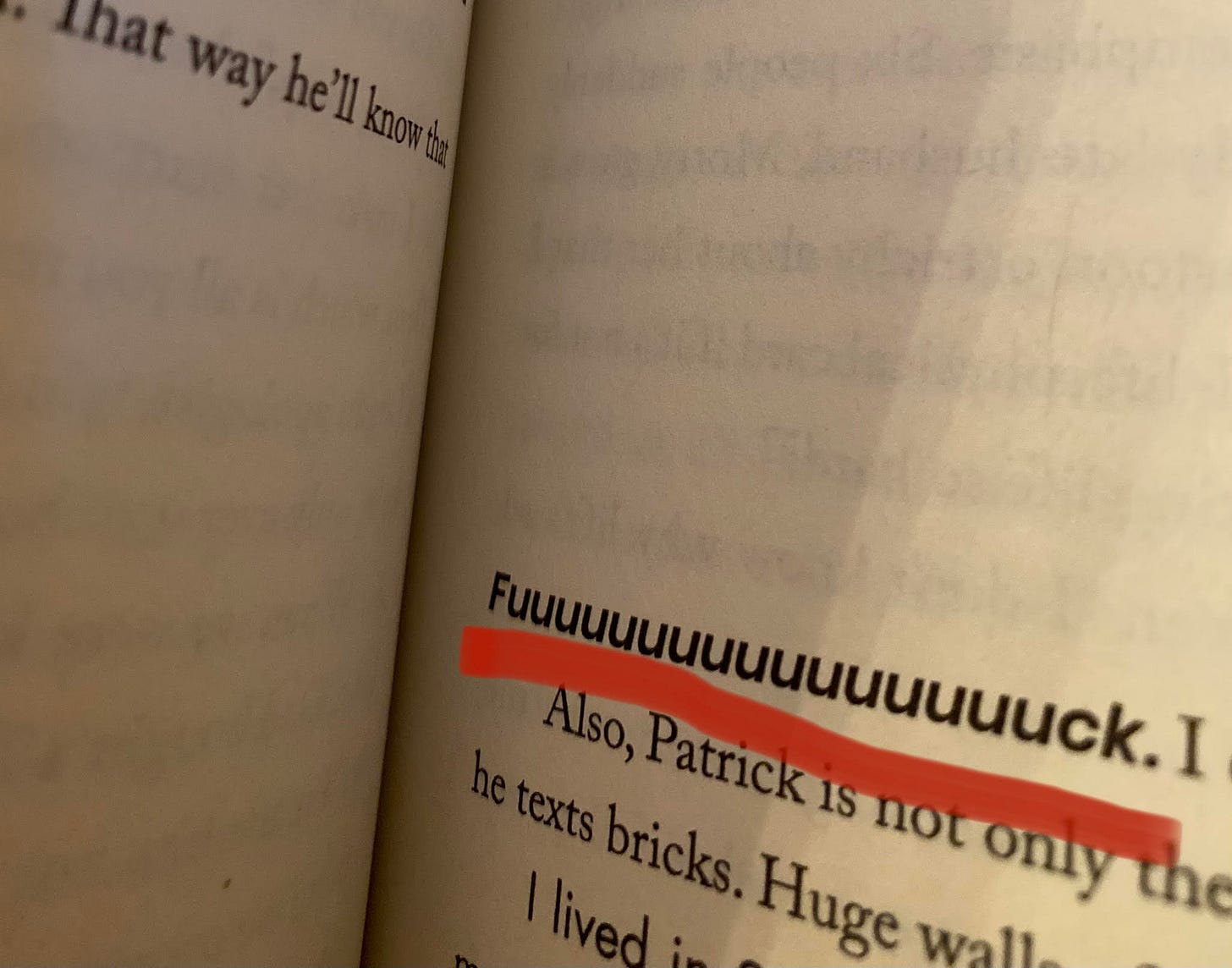

This week I read Mary H.K. Choi’s Yolk, a young adult novel about two 20-some Korean American sisters, and I was reminded of the anxieties of youth that bleed into adulthood. Of how even our inner narratives are steeped with the pressure of another’s gaze – like we are watching someone watching us and then twisting both from and for a chain of puppets. The intricate mental gymnastics and shenanigans the main character Jayne goes through are what one could call “cringey” (see: the inner monologue below), but my recoil perhaps comes from what Glenda Carpio, a professor of mine from college, and then referenced by Cathy Park Hong, calls the “shock of recognition.” When a hardcover book I hold in my hands documents Hinge swipes, Instagram story views, and self-flagellation for saying the perfectly wrong thing, I can’t help but laugh. It’s so apparent what is happening, so inarticulably embarrassing to read, that we crinkle and crumble and claim that it’s probably far-fetched and overblown.

Though after devouring this book like junk food in less than 24 hours and guffawing at these delightfully millennial moments, what stands out to me is Jayne’s desperation to make herself known – and not like the Mean Girls grungy crew fighting back, but in a much more recognizable way. Because even outsiders have the benefit of being an antithesis, of being the flip side to what’s en vogue and having something to push against, a ground to spring away from. Growing up as an Asian American woman, as Choi parses, is often times about being invisible. I felt the shock of recognition reading Jayne’s thoughts because amidst my cringing, I knew that feeling of transparency: the expectation to not be seen at all.

It’s a unique feeling moving through life assuming no one remembers you. It is when I go to the weekly compost station and the kind young woman there says “Hi Annie!” and I still gasp every single time under my mask; it’s when I finally meet a new internet friend unexpectedly and feel the urge to point to myself and say, “it’s me”; it’s seeing people in my industry knowing full well we have met and leaving the possibility open for it to be the first time because I can almost fell the oncoming “nice to meet you.” Most devastating of all is that none of this glazing over surprises me. I have gotten so used to seeing myself from a distance seeing someone else seeing me again that the strings of that puppet charade have all but merged into reality.

Reading Jayne’s story was watching her wrestle out from under zip-tied wrists. Adulthood has been a complicated journey of figuring out how to reckon with this feeling of being looked through. Because to rebel is to react to the norm, and in some ways reject what comes naturally to me, whereas I just want to exist, for the storybook blonde main character to look me in the eyes and say nice to see you again. Or actually, because they probably already do that more times now than I have come to believe, I need to extract the long tapeworm from my intestines that eats away at my physical being and deposits the idea that to be held in someone’s mind is a symbol of my worth. As if I am tallying the number of hits in the brains of those I encounter.

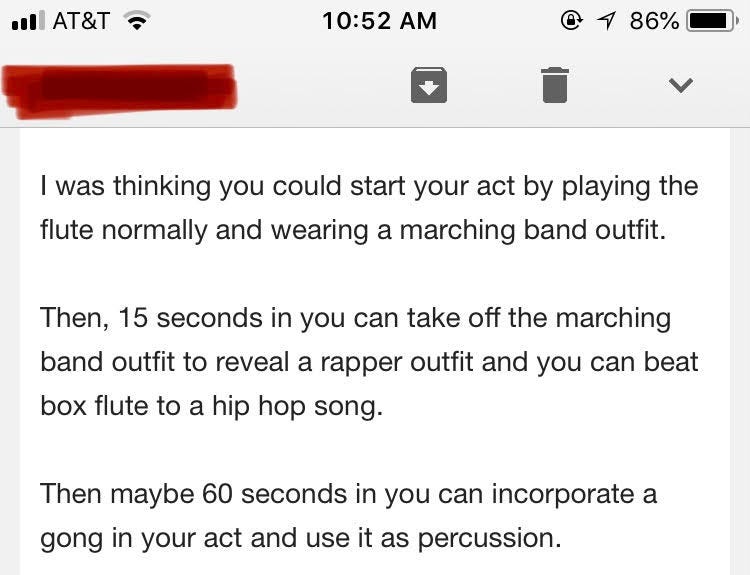

It’s this overlapping, messy string of gazes that makes the cringey and gimmicky in my life all the harder for me to accept without recoiling, stuffing them into a box, and sitting on top as they pound their way out. Like the time in high school I learned to beatbox and play the flute at the same time, and how the “cool factor” always felt like it was there because it was in relief to who I was before – unknown and now thrust in front of your face with some vocal percussion. This is really for when I write a scathing memoir, but the emails I got from national media outlets, mind you, ranged from mildly annoying to outright racist to highly dysfunctional (i.e. put on a band costume and play something square and then rip it off and you’re wearing a ‘rapper’ outfit underneath and then do your act). It was like I couldn’t be a person that did what I happened to do without needing to be the inverse of someone’s idea of who I should be – someone who never bothered to look at me in the first place. It’s something I’ve encountered in dating, in the workplace, in nearly everything I do. And it has made trying anything new heinously fraught as more and more puppeteers enter the picture so that I can’t even tell what’s me and what’s me rubbed out by someone else.

Cooking is safe. Cooking is new, but it is me inside my home eating for me and stirring for me. I’ve thought about how food is something in which my tastes and preferences aren’t up for interpretation – not like when I say I like classical music and happen to assuage people’s expectations versus when I say I had a viral internet past in beatbox flute or like Vampire Weekend and some annoying boy from a dating app pegs me as alternative. Even the phrase, “you have good taste,” feels subject to this same dynamic of someone else’s normal, and I chuckle now that I literally have “bad taste.” But what tastes good to me is truly my own - I can like dank pickles and LuoMiGi and pineapple on my pizza and it’s no skin off your back. It’s somewhere I can be creative each day and actually feel generative, without the pressure of making a product and collecting approval because by the time I post my food chronicle on Instagram, the meal is already sitting in my tummy, like it or not.

The day I first wrote about my food journey, I felt my heartbeat in my throat. I obsessively refreshed my Instagram to gauge reactions. Because for the first time in a long time, I was free falling. I didn’t know what people would think. There wasn’t a precedent like for the hundreds of flute concerts I’d prepared for to the point where once I saw a crowd, I’d know roughly the feeling of their response. I was less worried about revealing that I had COVID - which was shameful in its own separate way - and more anxious that I would be pegged yet again as something fully digestible: someone who lost their smell, a gimmick and a label that temporarily mapped me into people’s minds.

And what strikes me now and always when I think about this is how vain it sounds on paper and how quick I am to deem it so, when really, moving through life thinking and truly believing, and often times getting proven right, that nothing you say to someone new will stick is akin to being ground down to a dust. These last months have been about me tossing that dust up. It’s about me learning to let go of this complicated network of strings I’ve held up around me and looking at myself in the face. Because ultimately, I’m the master puppeteer at the top letting those around me hang on and pull me down. It’s been about realizing that I can both not have smell and be a cook when, and if, someday I get it back. It’s less about throwing middle fingers up at anyone who thinks there’s a hip hop side of me in a grossly racialized way and more about me untying that idea’s connection to my choices - recognizing that these forces are out there but how I exist in other people’s minds is not a string I can pull, and learning that being aware of the implications of myself on others isn’t the same as letting them tie a ribbon around my throat.

The darkest cooking thought that seeps in is the same as all my others. That I am a fraud and that what I do is only interesting because it has that glean of the unexpected. But I’m working on tucking that away. I’m working on really noticing that all the chefs I admire are writing books about themselves and how their food falls into their own life stories in their own words. I could care less about how it tastes when I’m reading – imagining their dishes in their hands, “exactly how they like it” as my new friend Kate writes, is what cooking is about. Ironically, oversharing every meal of mine and these entangled thoughts is my way of rejecting approval. By sharing what feels true even while it’s still fresh, I’m looking at myself from within myself. I’m forcing out the words, and maybe cringing a bit, but then prying my eyes open and realizing that I’m still standing.

Leave me a comment if the spirit moves you. To those reaching out, it has been special hearing your thoughts!